words DOUG GEYER | photography DEOGRACIAS LERMA

Alexandre Farto is a world-renowned street artist from Lisbon, Portugal. For years, his work has been featured in museums across the globe, and in 2015 it even ventured beyond our earthly limits into outer space aboard the International Space Station.

He adopted the moniker “Vhils” in the early 2000s as he plied the first manifestations of his vision through graffiti. While primarily known for his dynamic bas-relief carving on walls in public spaces, Vhils also incorporates seemingly disparate materials from the everyday world of anonymous, working-class citizens.

Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center has had the honor of hosting Vhils’s first large-scale exhibition in the United States. Haze opened on February 21, 2020 and was extended due to the pandemic with an upcoming closing date of February 28, 2021.

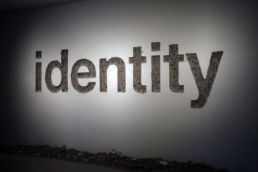

Haze “seeks to address the vagueness and obscurity, the chaos and ill-reflected direction that our interconnected global societies are following based on a model that is fundamentally flawed and mathematically impossible to sustain in the name of short-term material comfort, whose impact and consequences—both to ourselves as a species and to the very planet we call home—we either ignore or refuse to acknowledge.”

Polly had an opportunity to chat with Vhils and tour the exhibition just before opening night last year. Here’s a glimpse at our conversation.

Polly: You seem to be a chronicler, not a critic. You sort of freeze and capture the essence of what is going on in a certain place.

Vhils: Yes, in a way, with materials from the cities where I go. And also, with the impact of globalization. The first piece in the video, [in reference to the video in the exhibit] you have a very slow-motion video that goes from Shanghai to Cincinnati to LA and to Paris. Sometimes you don’t really know where that city [has evolved] from, or the kind of globalization that evolved in the last fifty years. [Globalization has] given us a lot of good things and positive things, but at the same time it brought kind of an [introduction] of brands. The cities are different, and the cultures are different, but you incorporate the same logos. Even if the writing is in different languages, the products are the same.

But it’s not, again, as a critic. I think there’s a lot of good things that come from this world, and we send each other the same codes, the same language. The world is in a period of time with the most peace. But it’s more like capturing the moments of now, because I think things are really mixing and connecting right now. What I try to do is really slow down the base of the cities and try to reflect the everyday life that we have and reflect on the impact of the involvement being taken by every side of the world.

P: Sort of like globalization, technology—phones that you can use to take pictures, FaceTime, Instagram, Snapchat—is used to speed up our interactions and things go really quickly. So, enters the idea of ‘let’s slow this down.’

V: Yeah, and you know, reflect on the beauty of everyday routine, the beauty of everyday people, the beauty of. . . The first piece is really a slow down. It’s a slow motion of the cities, and then I see the rest almost as stills of fossils of the current contemporary times that I grab from cities, and then put everything together to try to internalize these moments and make people step back and think.

P: I find it fascinating to go below the surface. That idea of being an artistic archeologist.

V: I don’t try to. I don’t want to be. I hope it has an impact, but it’s more like a process of thinking. But sometimes when you do this kind of thinking it’s like. . . I don’t try to be too pretentious about it and not judging because it’s very difficult when you’re digging into history not to take a side, but it’s very interesting to bring that history back, and in that process, I can imagine it’s a very good analogy. Everything, the city is kind of a constant buildup of layers. And this act of destruction to create, that’s a cycle that is permanent in all of humanity.

P: There’s a famous saying: ‘if these walls could talk.’ In essence, that sort of strikes me as your way through the jackhammer, the chisel, the explosion. You’re not trying to say as much, but you’re trying to let the walls talk. Would that be accurate?

V: Yeah, and from the walls and all the elements, I try to bring the city inside. I’m trying to make them talk in a way. That’s what I’m trying to do with every aspect of things.