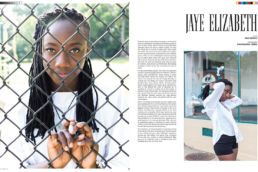

words DANA JOHNSON | photography DEOGRACIAS LERMA | photography assistant SARAH COCHRAN | makeup artist CHRISTINE RICE

Within seconds of my entering her warmly decorated and sunlit apartment, Sharon Draper is on the hunt for something she wants to show me. There on a dark end table is the object of her search—a copy of Hamilton: The Revolution, Lin-Manuel Miranda and Jeremy McCarter’s book showcasing the

goods and chronicling the success of Miranda’s Pulitzer-prizewinning drama.

“Ah!” Draper says as she comes upon the hardcovered gem. Eager fingers reach for it, pancakesmooth cheeks smiling, crinkles just at the corners of her eyes, parenthesizing the twinkles. “Oh, my goodness, it’s the entire libretto. It’s the whole thing—what he was thinking, why he included this, and why he left that out. A letter from him to Angelica. This [Miranda] was a man who thought, who read, who wrote. This is why we have to teach children to think and to read and to write—because that is where the great minds are.”

And our conversation begins. It requires no formal ice-breaking, no testing of waters with small talk, no hiccupping starts and stops.

After a brief tour of Draper’s home, including the cocoon of an office lined with papers and photos and books, we settle in the living room on the couch built for comfort. Draper conveys an open welcome and goodwill, the same vibe that comes across from an old family friend who hasn’t seen you in a while.

A Cincinnati transplant from Cleveland, Ohio, Sharon Draper was named Ohio Teacher of the Year and National Teacher of the Year in 1997, during her time as an English teacher at Walnut Hills High School. Her classes were in high demand from students and parents alike, but more than teaching language arts, Draper was teaching her kids about life. She lights up, saying, “I was the teacher that would have my room open at lunchtime. The kids would come in, and we’d have conversations and sit around. I was there for them, but I was hard on them.”

A Cincinnati transplant from Cleveland, Ohio, Sharon Draper was named Ohio Teacher of the Year and National Teacher of the Year in 1997, during her time as an English teacher at Walnut Hills High School. Her classes were in high demand from students and parents alike, but more than teaching language arts, Draper was teaching her kids about life. She lights up, saying, “I was the teacher that would have my room open at lunchtime. The kids would come in, and we’d have conversations and sit around. I was there for them, but I was hard on them.”

Exemplary service in her first profession as an educator has led Draper to the White House to be honored by presidents, to conferences from Russia to Guam to share her wealth of knowledge and unflagging enthusiasm with fellow teachers, and to countless schools to engage with the children within. Any talk of teaching, especially children, and Draper becomes more radiant, even as she talks about the difficult lives many of her students have faced. “Kids, many of them, have a lot of pain. They live surprisingly unhappy lives. And you have to be aware of the children that you’re responsible for. The kids who have difficulties, trauma, pain—they each come to you with a story, with an individual life.”

And Draper takes something from each of them, adding, “Good teachers learn from their kids as much as they teach. You must be willing to learn from your students, [or] you’re not a teacher.”

In a funny twist, it was her own students who challenged, encouraged, and demanded more from her, pushing her solidly into writing. Up until that point, Draper had written some poetry “for fun,” taking part in a women’s writing group. That involvement allowed Draper her first opportunity to read her own work aloud onstage. She experienced a feeling of exultation and was hooked.

In some ways poetry was a door opener, but it wasn’t until a mouthy student dared her to enter Ebony magazine’s annual Gertrude Johnson Williams Literary contest in 1990 that Draper learned what turned out to be her own life-changing lesson. Still tickled years later, she tells me that her three-page short story, “One Small Torch,” a first attempt at writing, won first place over several thousand entries.

She realized then that she could do more than teach writing; she could write. And it came easily.

“I believe I was given a gift—I don’t know how or why.” The words flowed from Draper, with her not understanding it to be unusual in any way. Inside, she held a story about young lives struck by tragedy, and Tears of a Tiger came spilling out in an untraditional form, in letters and homework assignments and overheard conversations of characters in the book. Draper had likely been touched by the untimely death of a student in her own life, as often happens in time in a high-school setting. Still, she shares that she truly does not know how the story itself developed within.

I ask who had been allowed to lay eyes on this first book, to give feedback and guidance along this yet untrodden course, and was not surprised to hear the response: “My students.” Draper released her words to them in sections, not letting on that she was the writer, but it wasn’t long before they were on to her. Her cheering section and on-site focus group, a perfect sample of the intended audience, worked with her on the first draft and through several more, with a couple of teachers and her husband, a deliberate and thorough reader, also pitching in.

Draper submitted the manuscript to twenty-five publishing companies and received twenty-four rejections. Simon and Schuster, the last company to respond, accepted.

Tears of a Tiger made its debut in 1994 and the following year was named the first Coretta Scott King Genesis Award recipient, an honor for promising talent in writing or illustration.

Tears of a Tiger made its debut in 1994 and the following year was named the first Coretta Scott King Genesis Award recipient, an honor for promising talent in writing or illustration.

Forming the Hazelwood Trilogy, Tears of a Tiger was joined by two more books, Forged by Fire and Darkness Before Dawn, each receiving accolades from readers, critics, schools, and literary entities alike. All this, and Draper was still teaching fulltime. Four books were published before she left the classroom for good after about thirty years of teaching at Walnut Hills and two other public schools earlier in her career. She is quick to point out that she did not retire because she had made a lot of money; she stopped teaching because she had accumulated enough years to retire. “Writers are not rich! Now, J. K. Rowling is rich. But they don’t make sections of amusement parks for people who write realistic fiction.”

The twenty-nine books now under her belt include titles for young, tween, and teen readers, educators in need of inspiration, and poetry lovers. Each give testimony that the words keep flowing. She amazes herself.

“When I’m not traveling, I try to write something. I start early, maybe around four in the morning, and I can go all day. Writing is not exciting. You sit in a chair and you write—that’s it. I read books, I research, I get up and get butter pecan ice cream, and I write.” Draper’s speech is punctuated by the soft thuds of her fingers typing taps out on the wooden table. “I can’t do much after six o’clock [in the evening]. I start writing mush. Then it’s time to go watch Scandal or something.”

That is not to say that all the ideas and thoughts that form in her mind, translated always in total silence, alight gracefully on the laptop screen. “The first draft of Stella by Starlight was horrible.” The author shares that her current editor is invaluably and brutally honest, showing pleasure for the voice here and pointing out the flaws there, seeing always through to the potential in a book.

Stella began with Draper’s grandmother, Estelle Mills Davis, her father’s mother. “She was born in 1905, I think.” What followed was a long life, one long enough for a visit from her granddaughter and the great-grandchildren to the farm where she lived. Before she passed away, she gave to Draper’s father, Vick Mills, a notebook that she had written in as a little girl and had saved all her life. “That’s just amazing, incredible. It was valuable to her,” murmurs Draper.

“Do something with this thing,” the grandmother requested of her son.

“Okay, Mama,” answered the son, who was known to be a storyteller in his own right, with Draper often hearing the words, “Did I ever tell you about . . . ?” coming forth from his lips, amusement in his voice.

Vick then gave the notebook to his daughter Sharon, appealing, “You’re a writer. Do something with this thing.”

And the daughter said, “Okay, Daddy.”

And she did. The small town, the one-room schoolhouse, the farm—all end up in the book. The visits to North Carolina as a child, the smell of the air, the feeling ofsitting up under grown folks on the porch drinking what started off as tea and listening to them tell stories on a summer night under the stars—all became her memories. And although Stella is not exactly Draper’s grandmother, “she is based on the essence of my grandmother, her need to write, the spirit of that town, of those people, of that community.”

Draper once thought that her muse was her mother, Catherine Mills, a woman who filled the house with song with her operatic-quality tones and who fostered an immense love of reading in the writer as a small child. Draper now thinks her muse has been the grandma who wrote in that little notebook. The writer plans to pay tribute to the other side of her family as well. “I’m going to write a book about my mother next, I think. It’s still very, very . . . nebulous in my head. She has a story, too—completely different from my father’s. I’m not quite ready to tell it, but there is a story there.”

In the meantime, Draper has other irons in the fire. “I just turned a book in, and I have no idea if it’s good or not,” she says. Just getting back into the writing groove after some time off, Draper appreciates that her editor is being gentle with her, like a patient fresh from the hospital, but her expression reflects that she is anxious for word about this new realistic fiction piece.

“It’s about a girl in the fifth grade who has issues, and that’s all I’ll say.” A question about the development of main characters coaxes Draper to elaborate on the project. “She’s cool. Girls will like her. [The book] covers a lot of social issues that middle-grade kids need to talk about. So, I put it on an eleven-year-old fictional character. We can talk about her issues, not yours. I think it will open some doors for conversation on things that many children suffer through but nobody talks about it.” Like many other of her realistic fiction works, Draper tackles the tough issues embroiling youth today—pregnancy, suicide, abuse—allowing children to talk about the hard issues safely, from a place once removed.

There is a parallel in the strong responsibility Draper feels for both the impressionable young people sitting in her classroom and those caught up in her books. With each, she portrays the real world without pushing morals bundled up in instructions of how to walk through it. “They sit there, and they look at you like those little birds behind you. They say, ‘Feed me, but don’t force-feed me.’” Mounted on the wall behind the dinette set is a beautiful Egyptian rug, colorful and handwoven, The Tree of Life. On it, a new bird grows, in stages, until it comes into its wings.

A knock at the door of the apartment breaks the thread of conversation. I turn to Draper in time to catch her animated face, eyes open wide with anticipation, before the words escape, “Oooh! Oooh! I hope it’s my dress!”

A knock at the door of the apartment breaks the thread of conversation. I turn to Draper in time to catch her animated face, eyes open wide with anticipation, before the words escape, “Oooh! Oooh! I hope it’s my dress!”

She opens the door, receives a package, and steps back inside giggling, overcome with elation. “It’s here! It’s here!” Then quieter, but all the while laughing, she says, “It sure is squished in this bag . . . I’m afraid to open it.” But she does, with tentative approval. “It’s got potential. But there’s no way I’m going to try that on until I’m here by myself—with the blinds closed. Just pray that it fits.”

I had glimpsed that the fancy ballroom dress is black and white and silky, but most important, it sparkles.

It seems that the writer is in love and learning to express herself in a new language, one different than of words. “I have had an incredibly blessed life. The writing, the teaching, the honors and awards . . . I’ve just been incredibly blessed. I am happy, and I like where I am, and I like what I’m doing. The one thing that I have never been able to do is dance. I’ve always had this secret yearning.”

The people closest to Draper, her best friend, her own children—one of whom is a professional dancer, a ballerina with her own studio, no less—know that Draper does not and cannot dance. But a coupon for a free dance lesson led her to the glass doors of Arthur Murray Studio on Montgomery.

The new relationship seems to have taken. Draper remains smitten after ten months of lessons, her voice softening as she describes the joy that dancing brings. “It makes me happy in a different way than anything else.” I listen to the litany of moves she now does: “I can do waltz, I can do rumba—not very well, but I’m doing it. I can walk on[to] the dance floor . . . ” She rises from the sofa, and I watch the delicate steps, the graceful turn, the light in her countenance. Her favorite is the waltz.

“I don’t see any reason to stop. I feel happy when I get to the [studio]. I feel accomplished when I leave. And I have no high expectations, it’s just that I’m getting personally better. I’m already doing things I never could have imagined I could do.” No longer merely an observer of the art of dance, she now partakes, savors, and delights in it.

Self-described as “artsy-fartsy” by nature, Draper acknowledges that her first love, the literary arts, still thrills. “Oh, yes. I do love reading! I don’t read as much as I used to.” She is still recovering from when she was a judge for the 2014 National Book Award, an obligation that required a long but fulfilling summer of reading the hundreds of books delivered in cartons to her house.

Also, while writing Draper sets aside a lofty stack of books, queued and standing by for a hiatus in her work. “I can’t read while I’m writing because the syntax and the ideas of the person I’m reading float into me. I don’t want somebody else’s syntax in my head while I’m writing. It has to be just me.”

Also, while writing Draper sets aside a lofty stack of books, queued and standing by for a hiatus in her work. “I can’t read while I’m writing because the syntax and the ideas of the person I’m reading float into me. I don’t want somebody else’s syntax in my head while I’m writing. It has to be just me.”

Possible projects continue to announce themselves to Draper, each vying for her attention. Draper shares that an intended project is to someday return to her poetry beginnings and write a book in verse, but she expects it will take quite a bit of work and some time to build up her confidence. “I’m in awe of Jackie Woodson [who wrote Brown Girl Dreaming]; I admire her. She’s a good friend. Unless I can write something that she thinks is good . . . I would almost need her to say, ‘You did good there.’”

Even as Draper gives a generous nod of appreciation to other writers of her time, she believes today’s successfulblack female writers owe a great deal—indeed, everything—to Zora Neale Hurston. Like Draper’s mother, Hurston was rooted in Florida and migrated North. “Even as a little girl, [Hurston] was looking up that road to go someplace else, do something else. She knew she was going to be something else . . . She was unusual because she was an outspoken, literary, black woman in the ’20s. She was writing, and she was creative, and she was outlandish, and she was bold—oh, my goodness, the stuff that woman did!”

Like Hurston, Draper has opened her own arms to opportunity, created her own paths. She is using her abundance of gifts for good, living a life, charmed. “I wake up every morning thanking God for these blessings—for this place, for where I am in my life, for being able to do this, for what we’re getting ready to do with this magazine, with that dress that I’m afraid to try on . . . ” Her laughter spurs on my own, and we fill with joyful sound the space of her apartment, her safe, cute little haven, a place of protection after the rainstorm.

“I see rainbows. I see sunshine. Even through tragedy. And I think that’s where strength comes from. It’s when you can still see the rainbows.”

To learn more about Sharon Draper, visit SharonDraper.com. Look for Blended, her latest book, in the fall of 2018.